Terror in the Red Sea is a Problem for Europe, But Europe is Playing Dead

- 3 ledna, 2024

Few in the Central European region perceive the Red Sea area as a potential security crisis zone, which could have catastrophic impacts on economic performance and the economic and security situation of the European continent in both the short and long term. Nevertheless, and especially after disruptions in part of the supply of raw materials (particularly gas and oil products) from Russia following its aggression against Ukraine, this part of the world is literally critical for our future. Unfortunately, neither at the level of national governments nor at the level of institutions such as the European Union or NATO are the threats there receiving adequate attention, in my opinion. Our negligence, or rather indifference, means that our future costs will be many times higher than they would have been with timely intervention. However, this is far from the first time in European history, and probably not the last.

World Economy and Maritime Transport

Although it may seem exaggerated from a Central European perspective, more than eighty percent of global trade is conducted through maritime transport. Despite being the oldest mode of transportation in today’s mix—maritime, rail, road, and air—it is absolutely irreplaceable. This is due to its unparalleled ability to transport the largest quantities of cargo at the lowest cost. Many types of cargo (such as natural gas, oil, coal, iron ore) cannot be transported between continents in reasonable quantities by any other means. With a slight exaggeration, it can be said that our (Euro-Atlantic) civilization emerged with the mastery of maritime transport, but it also means that it could collapse. Especially today, in a globalized world where we have developed an unhealthy dependence on the continuous supply of goods produced on the Asian continent (China, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan) and raw materials from the Arabian Gulf region (oil and liquefied natural gas). Moreover, this dependence is continuously deepening, often not only for economic reasons but now more than before for ideological reasons. This particularly involves the transfer of „dirty“ technologies or mineral extraction outside of Europe, which ultimately increases our vulnerability.

The negatives of such dependence became evident during the COVID pandemic, and especially after it ended, when there was an enormous increase in demand for shipping space. This, combined with the disruption of traditional supply chains, not only led to a sharp rise in prices but also the collapse of supplies of some key commodities. Another example of what a disruption in maritime transport means for global trade was the incident involving the container ship Ever Given in the Suez Canal in 2021. The ship, operated by the Taiwanese shipping company Evergreen Marine, blocked the canal between the city of Suez and the Great Bitter Lake for „only“ six days, yet the commercial damages were estimated at 9.6 billion US dollars.

The volume of goods transported by maritime shipping is also increasing, and according to UNCTAD forecasts, not only is demand for this type of transport growing, but it is accelerating and expected to be three times higher by 2050 compared to today.

The busiest maritime trade routes in the world in terms of the number of ships sailing are Asia – the east coast of the United States and Asia – Europe. The latter route is logically crucial for us in Europe and simultaneously passes through two „chokepoints“—the Bab al-Mandab Strait and the Suez Canal. If we add the Strait of Hormuz, we identify three critical points for the economy and everyday life of Europeans. It is not necessary to emphasize that all three are located in areas with limited geopolitical stability, and only one of them (the Suez Canal) is not within the immediate reach of a power that has long been hostile to us and our way of life. Yes, I am speaking of the Islamic Republic of Iran, a regional power with significant military strength and rapidly growing political ambitions in the region.

Geographical Definition and Area Description

The Bab al-Mandab Strait is the gateway from the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea and, in addition to separating seas, it also marks the boundary between the continents of Asia and Africa. Its name translates from Arabic as „Gate of Tears.“ Interestingly, within the Arab League, there is a sub-region called Bab-el-Mandeb, which includes three countries—the Republic of Djibouti, the Republic of Yemen, and the State of Eritrea. Despite this fact, all three countries engaged in several short wars in the 1990s due to unresolved borders.

Geographically, the strait is only 26 kilometers wide at its narrowest point, between Ras Menheli in Yemen and Ras Siyyan in Djibouti. Additionally, Perim Island further divides this already narrow passage into two straits: the eastern, known as Bab Iskender, which is 5.37 kilometers wide and 29 meters deep, and the western, known as Dact-el-Mayun, which is 20.3 kilometers wide and 310 meters deep. This effectively leaves a corridor for maritime transport with a maximum usable width of 18 kilometers. Just as there are different continents on both shores, there are also different states on both shores.

On the African side is the Republic of Djibouti, a relatively stable country with a semi-presidential system by local standards. Although it is not a democracy in the European sense, rather an authoritarian state, it provides its citizens with a poor but relatively peaceful place to live compared to neighboring Somalia. The country is predominantly Muslim (94% of the population), and due to long French colonization, French is used as the second official language alongside Arabic. Of interest to us is the presence of military bases of several countries. Historically, France has had the longest military presence here, having long considered Djibouti one of the most strategic locations in its defense concepts. It was not only about controlling the southern entrance to the Suez Canal but also at certain times providing a counterbalance to the British military presence in today’s Yemen. For these strategic military reasons, France only allowed Djibouti to gain independence in 1977.

Currently, permanent military bases of China, France, Japan, and the USA are located in the Republic of Djibouti.

The situation on the Asian side of the Bab al-Mandab Strait is significantly more complicated. This is the territory of the Republic of Yemen, the least developed state in Asia and today a de facto collapsed state. Given that it is a key territory in today’s conflict, it is necessary to discuss it in more detail. Yemen has been a key trade route since the first millennium BC. Over the centuries, its importance as a place through which world trade flowed did not diminish (although its wealth did not grow). The dominance of the Ottoman Empire over this territory, which lasted from the 16th century, ended with World War I when the independent Kingdom of Yemen was proclaimed. However, the British presence, which dates back to their occupation of the strategic port of Aden in 1839, was a major stabilizing factor for world trade here. Their dominance took many forms, but it definitively ended on November 30, 1967, with the withdrawal of the last British troops from the country. Like the French on the opposite shore of the strait, the British presence was primarily to ensure control over the entrance to the Red Sea, but unlike them, the British had an excellent port at Aden. The long-standing division of Yemen was one of the reasons for the conflicts after the British departure, the other being its religious division. Although only one percent of Yemen’s population does not identify with Islam, the rest of the population is roughly divided 60% to the Sunni branch and 40% to the Shia branch of Islam. These dividing lines led to the Yemen-Yemen war of 1979 and the de facto renewed civil war of 2012.

The last country geographically involved in the Bab al-Mandab Strait area is the State of Eritrea. It is mentioned more for completeness. I do not anticipate the use of Eritrean territory for attacks on maritime transport, nor for operations to protect it. Eritrea is exhausted by a long and bloody war with Ethiopia, has demographic problems (significant emigration of its population), and especially economic issues. Its budget and necessary infrastructure projects are largely funded by countries interested in maintaining peace and free navigation in the area.

Historical Development in the Area

To understand the current situation, it is crucial to follow the historical development since 1869, when the Suez Canal was opened and the Red Sea ceased to be a „dead end“ ending in then-poor states. Since then, the Suez Canal, the Red Sea, and the Bab al-Mandab Strait have been one of the most strategic areas of the modern world. This has corresponded with the interest of world powers (which have changed over time) and regional players in controlling or at least influencing movement in local waters. While at the end of the 19th century the dominant players were two European colonial powers—France and Great Britain—over time, the voices of Italy, Ethiopia, and Egypt were also heard. The swan song of European countries in terms of influence in the area was in 1956 with the Anglo-French operation Musketeer. Under the pretext of separating the warring armies of Egypt and Israel, it meant reoccupying the Suez Canal zone after the withdrawal of British forces in the area in 1954. However, this operation fully demonstrated the shift in world power from former European colonial powers to the bipolar division of the world along the USA-Soviet Union axis. Incidentally, the oil export embargo declared by Saudi Arabia against Great Britain and France following the Musketeer operation was the first use of this powerful economic tool.

This first military conflict in the Suez Canal area was unfortunately far from the last. After the closure of this waterway from 1956 to 1957, another closure followed from 1967 to 1975 as a result of the Six-Day, War of Attrition, and Yom Kippur wars. Incidentally, since 1967, in addition to fourteen ships from other countries, the Czechoslovak river-sea ship Lednice was also involuntarily held hostage on the Great Bitter Lake.

In contrast, the southern part of this route, in the Bab al-Mandab Strait area, has not yet been significantly affected militarily, except for the battles between Great Britain and Italy during World War II.

Key Players in the Current Crisis

Iran (through the Houthis) is trying to present the current escalation as a response to the Israeli reaction to the massacre carried out by Palestinians on October 7 and the subsequent military action by the Israeli Defense Forces. However, to understand the current situation, it is essential to describe events since the beginning of the latest civil war in Yemen, which broke out in September 2014. Already then, Iranian interest in this region became evident.

This conflict was just as bloody and rich in casualties on both the fighting armies and militants, as well as civilians, as is unfortunately customary in this part of the world. After initial support for the coalition led by Saudi Arabia from the USA, Great Britain, and France, it was limited due to media pressure and campaigns by some non-governmental organizations. Later, after a series of ballistic missile and drone attacks, which were undoubtedly backed by Iran, and the overall war fatigue, where neither side could achieve a decisive and clear victory, the intensity of fighting has decreased since the end of 2022, with both sides seeking ways to end the war.

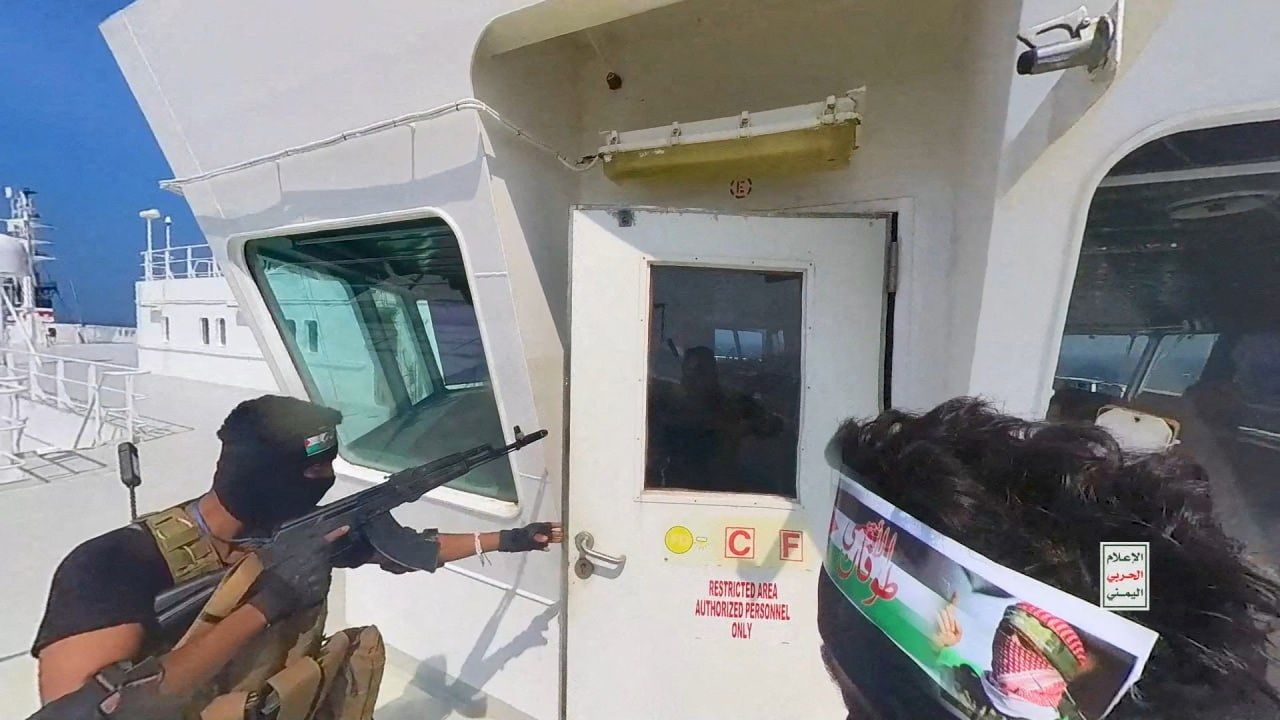

The beginning of Iran’s (through the Houthis or under the cover story of Houthi rebels) current war against ships in the Bab al-Mandab Strait can be dated to October 17, 2023. The range of these attacks is relatively broad, with the most common being the use of „suicidal“ drones with varying results. From missing targets to drones being destroyed by military vessels in the area, to successful attacks that so far have always ended with „only“ damage to ships. The pinnacle was the helicopter drop of „Yemeni militants“ on the Galaxy Leader ship and its subsequent hijacking to the port of Hudaydah.

Such a situation is unsustainable in the long term, not only from the usual and legal practices in international relations but also from the negative impacts on the world economy. After three „blows“ that have recently hit it (COVID, Russian aggression against Ukraine, Palestinian terror), it could have incalculable consequences. The current problems, such as delays in maritime transport and rising costs, are just initial warning symptoms.

In response to this situation, the USA decided to launch Operation Prosperity Guardian, which aims to protect maritime transport, particularly in the Bab al-Mandab Strait, but also in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. The attempt to form a coalition of forces and means has so far met with little success.

Of the forces willing to participate in Operation Prosperity Guardian, it is important to note that relevant military strength is currently provided only by the USA, Great Britain, and Greece. Other countries are contributing mainly by sending observers.

What Could Happen Next?

What can we expect next? I can imagine a number of scenarios, but I will present two. The first, in my opinion, optimistic scenario is currently unrealistic, even though it would benefit everyone except the attacker.

In the current escalation, apart from Iran and Russia, none of the major players stand to benefit. China may perceive the further strain on American armed forces positively, but even that does not yet mean a weakening of American military capabilities in the Pacific, where it is crucial for China. On the contrary, China, which conducts a significant portion of its trade through this area, suffers from any economic instability. China is interested in maintaining the best possible relations with Sunni countries in the Arabian Gulf, especially with the leader of these countries, Saudi Arabia. Last but not least, this negative development goes against the already disrupted Chinese project One Belt One Road. China’s involvement could not only avoid losses but also increase its political influence in the region, boost respect for its armed forces (and particularly the navy would gain invaluable experience), and ensure the uninterrupted flow of goods on which the Chinese economy is vitally dependent. For its involvement in the coalition, it would be necessary to find a balance between the USA and China, as neither superpower would want to appear to be in a „subordinate“ role to the other.

To implement the optimistic scenario, it would be necessary to form a truly strong international coalition, which, in addition to the two world superpowers—the USA and China, would also include key players from the Sunni Arab world and the European Union member states along with Great Britain. Its military operations would have to include both massive attacks from the sea and the deployment of ground forces.

Such a coalition could not only ensure free navigation in the Bab al-Mandab Strait but also resolve the long-term instability in Yemen. This could be achieved by effectively dividing Yemen according to religious lines and restoring the existence of two independent Yemeni states.

Unfortunately, given the current alliance between Russia and Iran, it is necessary to anticipate that Russia will use its veto power in the UN Security Council to block joint action with a UN mandate.

The military capacity of such a coalition, as well as its political and economic influence, would clearly signal to Iran the unsustainability of military intervention, and there is a high probability that the Houthis would be left alone in such a conflict, with Iran shifting its proxy activities elsewhere, for example, to Iraq, Lebanon, or Syria.

Unfortunately, I fear that we will end up with a more pessimistic outcome, which will not bring a long-term solution to the situation.

Despite peace in the area being in the vital interest of the European Union, it is also leaving its resolution to the USA in this crisis. Even though naval units from some European countries are already operating in the area.

The current deployment of allied naval forces, according to my pessimistic scenario, will remain purely defensive. Such a way of waging war will be highly inefficient and financially costly, but given the current political constellation, it is the only feasible option. This is due to both a relative lack of forces and political considerations. Political considerations are twofold: local concerns about an Iranian reaction in other parts of the region, such as the Arabian Gulf or Iraq, and domestic concerns about the upcoming presidential election in the USA. The Biden team certainly does not want to enter the election with another war, another extraordinary increase in military spending, and especially not with images of wounded or dead American soldiers. In contrast, Iran has every interest in escalating the situation because, unlike American politicians, the ayatollahs in Tehran do not have to answer to voters, and because images of dead and wounded Yemenis in the world’s media can only help them in their fight against the USA. Any damage to the USA will also play into the hands of Russia, one of Iran’s few allies.

As for the position of the European Union, its long-term program in international crises is to try to „buy“ its way out by printing new money and sending it to anyone interested. Additionally, some member states, France and Germany, still have efforts to weaken American influence. Once again, this benefits China, Iran, and Russia. The result could be that the USA will continue to focus only on its interests, on protecting maritime navigation between the Arabian Sea and the USA. The weakening of the Euro-Atlantic bond will continue, negatively impacting American defense capabilities and military planning in Europe.

We are not heading for peaceful times, and our disinterest and unwillingness to defend our own interests, even by force, will soon catch up with us.

©2024 Milan Mikulecký. Všechna práva jsou vyhrazena.